Turning Existing WebAssembly Applications Into Distributed Programs

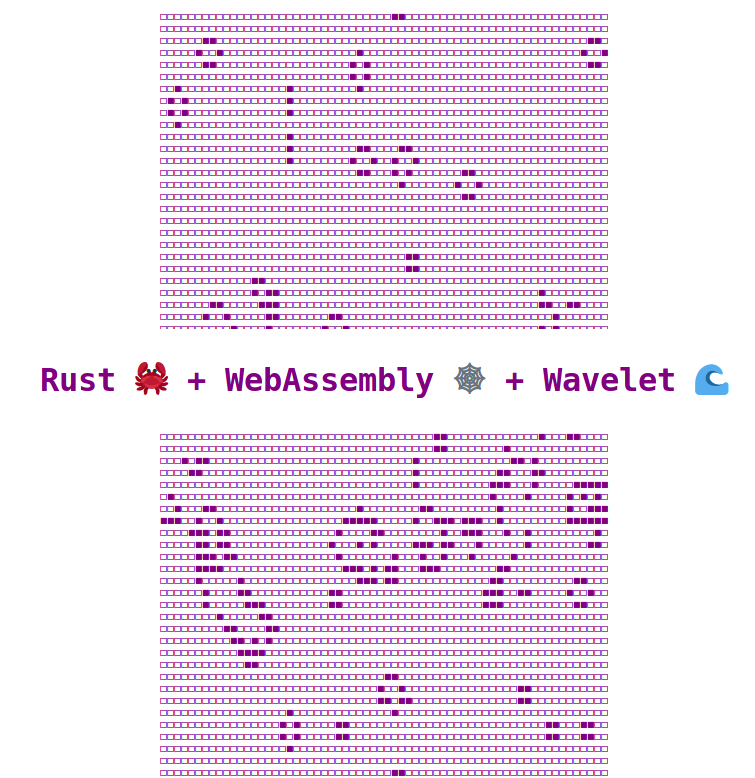

Or, how to make an eternal Game of Life Simulator.

One of the benefits of WebAssembly that we keep going on about is the ability to re-use existing code.

There have been a couple of articles demonstrating how easy it is to build WebAssembly applications that run on the decentralized virtual machine/smart contract platform Wavelet, but it hasn’t been shown how easy it is to port existing applications yet.

In this article, we’ll take the great Rust and WebAssembly Book’s Game of Life implementation, and run through the things you have to change in order to have it run on Wavelet, and end up with your own eternal cellular automata universe.

You can see a deployed version of what we’ll be building here and the final source code here.

Setup

We can use the exact same setup process as described in the Rust Wasm tutorial setup and hello world stages, with the minor difference of adding 2 dependencies to Cargo.toml, namely:

smart-contract = "0.2.0"

smart-contract-macros = "0.2.0"

We don’t need all of the things the setup includes, but we aim to stay as close as possible, so we will keep them in place.

Interfacing with Javascript

The first WebAssembly implementation detail the Rust Wasm tutorial goes into, detailed here, covers how JavaScript interfaces with WebAssembly and vice versa — this is different in Wavelet apps, and significantly changes how you write the frontend.

Rust Wasm uses the

#[wasm_bindgen]macro to export references in a way that can be called from JavaScript, and prefers direct memory access to the WebAssembly VM for high-performance updates.Wavelet uses the

#[smart_contract]macro to make functions in a single struct accessible to the wavelet-client library. Direct memory access is not recommended, as the bottleneck for wavelet application performance is not at the serialization/deserialization level, but at the Wavelet consensus level.

Interfacing with Game of Life

The Book’s implementation uses a single array to store the universe in WebAssembly linear memory — we will do the same. We will also use the same string format to render the game. Direct memory access is also possible, but not explicitly supported, so we do not get the same easily importable bindings that we see in the Rust Wasm tutorial and it is slightly trickier to access.

Rust implementation

This is the cool bit — we can copy all of the code directly! We only need to make two minor modifications — removing the #[wasm-bindgen] macros and adding a smart contract struct that will expose the Universe functions to wavelet:

use smart_contract::log;

use smart_contract_macros::smart_contract;

use smart_contract::payload::Parameters;

// The contract will store an instance of the same Universe struct implemented in the tutorial

// we also have a "stepped" construct that checks whether someone has already stepped the contract in a given consensus round

struct Contract {

universe: Universe,

stepped: [u8; 32],

}

#[smart_contract]

impl Contract {

pub fn init(_params: &mut Parameters) -> Self {

Self {

universe: Universe::new(),

stepped: [0; 32],

}

}

pub fn step(&mut self, params: &mut Parameters) -> Result<(), String> {

// only step once per round

if self.stepped == params.round_id {

return Ok(())

}

self.stepped = params.round_id;

self.universe.tick();

Ok(())

}

pub fn render(&mut self, _params: &mut Parameters) -> Result<(), String> {

log(&self.universe.render());

Ok(())

}

}

// ... the rest of the code in the Rust Wasm tutorial https://rustwasm.github.io/docs/book/game-of-life/implementing.html#rust-implementation

Rendering with JavaScript

At this point, the implementation diverges significantly. In the Rust Wasm tutorial, they utilize wasm-pack’s bindings to directly import the compiled rust code into their HTML + JavaScript frontend; we need to go through a few more steps; first to upload our compiled wasm to the distributed VM, and then writing the connector code that will instantiate the VM locally and synchronize it with the global state.

We will try and stay close to their implementation, and highlight the core differences.

First, we need to upload the contract so that we can access it in the frontend. We can follow the same steps as detailed in the decentralized-chat tutorial, just use the wasm-pack build command to generate your .wasm file, and use the wasm_game_of_life_bg.wasm file in the pkg folder in the root of your project.

To interact with the uploaded program in JavaScript, we need to add the wavelet-client & jsbi dependencies with npm i -s wavelet-client jsbi or yarn add wavelet-client. With these dependencies, we are good to start coding.

Our implementation is pretty simple, at only 40 lines of JavaScript and HTML.

The HTML stays pretty much the same, except that we import the index.js file instead of the bootstrap.js file:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Game of Life</title>

<style>

body {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

left: 0;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

display: flex;

flex-direction: column;

align-items: center;

justify-content: center;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<pre id="game-of-life-canvas"></pre>

<script src='./index.js'></script>

</body>

</html>

The JavaScript code is a bit more verbose, compared to the 9 lines of code in the Rust Wasm implementation.

In the index.js file, we first import the wavelet-client and jsbi dependencies.

import { Contract, Wavelet } from 'wavelet-client';

import { BigInt } from "jsbi";

We then initialize the Wavelet client, load a wallet from a private key that will be used to sign the transactions that progress the state of the simulation, and configure the contract object that will allow us to interact with the deployed code.

const host = 'https://testnet.wavelet.net';

const contractAddress = /* address of your deployed contract */;

const wallet = Wavelet.loadWalletFromPrivateKey(/* private key of a wallet containing at least 10 million PERLs - join our Discord and we will provide you with the neccessary funds*/)

const client = new Wavelet(host);

const contract = new Contract(client, contractAddress);

We will render the resulting string to a simple preformatted code DOM element, so let's get a reference for future updates.

const pre = document.getElementById("game-of-life-canvas");

We need to initialize the contract, which will fetch its memory state from the distributed VM.

contract.init().then(r => {

Once it is finalised, we can interact with it in two ways, either by calling functions or testing them.

Calling functions execute them on the distributed VM, and changes the global state, and requires transaction and processing fees. As you can run a Wavelet network locally pretty easily, or get testnet PERLs for free, this will not cost you anything, but still incentivizes you to write efficient code.

We recommend 10 million testnet PERLs at this point, as Wavelet hasn’t set its decimal precision yet — in reality this algorithm will require a tiny fraction of a mainnet PERL to run, resulting in a cost comparable to an AWS Lambda function execution.

Testing functions execute them on the local VM, using the VM’s current memory. It is free but does not result in any persistent changes in VM’s state.

We use test to call the render smart contract function, which will return a string in the resulting logs. All serialization/deserialization happens through this log interface, similar to CLI applications:

const results = contract.test(wallet, "render", BigInt(0)).logs[0];

We then set the textContent of the pre tag to be the resulting value, which will give us a visual representation of the Game of Life universe

pre.textContent = results;

});

Up until this point, we only get a single, static snapshot of the universe. We need to register to changes in state in order to get a dynamic world — changes in state in the distributed VM is known as “consensus rounds” — where a subset of nodes agree that a given set of transactions are legitimate.

We register to consensus events and synchronize the contract’s memory on each round. We then render the current state as before, and finally call the step function, which will advance the state of the universe by one tick.

client.pollConsensus({

onRoundEnded: _ => {

contract.fetchAndPopulateMemoryPages().then(_ => {

const results = contract.test(wallet, "render", BigInt(0)).logs[0];

pre.textContent = results;

contract.call(wallet, 'step', BigInt(0), BigInt(1e7), BigInt(0));

});

}

});

That’s it! A working Game of Life simulation that can evolve for as long as there are nodes connected to the distributed VM.

Of course, it's not a lot of fun yet, as it isn't interactive - the Rust Wasm tutorial first showed how to implement canvas based renderer before detailing how to toggling cell states - lets tackle that next.

Adding interactivity

In order to achieve this, we need to change both the Rust code and the HTML + JavaScript frontend.

Following the tutorial, we will first add a button to run and pause the simulation.

We add a button, just before the <pre> element in index.html:

<button id="play-pause"></button>

We then add a variable in index.js to track whether the game should be running, and some logic to change the variable and check it when trying to advance the universe:

const playPauseButton = document.getElementById("play-pause");

let running = false;

const play = () => {

playPauseButton.textContent = "⏸";

// calling the step function will trigger consensus, and therefor the render loop

contract.call(wallet, 'step', BigInt(0), BigInt(1e7), BigInt(0));

running = true;

};

const pause = () => {

playPauseButton.textContent = "▶";

running = false;

};

playPauseButton.addEventListener("click", event => {

if (running) {

pause();

} else {

play();

}

});

// replace the old client.pollConsensus call with

client.pollConsensus({

onRoundEnded: _ => {

contract.fetchAndPopulateMemoryPages().then(_ => {

if(running) {

const results = contract.test(wallet, "render", BigInt(0)).logs[0];

pre.textContent = results;

contract.call(wallet, 'step', BigInt(0), BigInt(1e7), BigInt(0));

}

});

}

});

// kick start by calling play()

play()

This should allow us to start/pause the simulation. One interesting aspect is if someone else is busy simulating the universe, the state will still update, so pressing play may show you a significantly different world on the next render.

You can choose to change the behaviour by moving the rendering code that is in the consensus callback out of the if statement.

Toggling cells

This requires new functionality in the rust code; we can implement it in the same way as described in the tutorial but need to expose the functionality via our contract.

// inside "impl Contract"

pub fn toggle(&mut self, params: &mut Parameters) -> Result<(), String> {

self.universe.toggle_cell(params.read(), params.read());

Ok(())

}

Once we have made the changes, we need to re-deploy the contract and update the JavaScript code with the new contract address.

Our frontend implementation is pretty similar to the Rust Wasm tutorial implementation, except that we still use the <pre> tag implementation, and call the Wavelet contract instead of the imported Wasm code

pre.addEventListener("click", event => {

const boundingRect = pre.getBoundingClientRect();

const scaleX = 64 / boundingRect.width;

const scaleY = 64 / boundingRect.height;

const canvasLeft = (event.clientX - boundingRect.left) * scaleX;

const canvasTop = (event.clientY - boundingRect.top) * scaleY;

const row = Math.min(Math.floor(canvasTop), 64 - 1);

const col = Math.min(Math.floor(canvasLeft), 64 - 1);

contract.call(

wallet,

"toggle",

BigInt(0),

BigInt(1e7),

BigInt(0),

{

type: "uint32",

value: row

},

{

type: "uint32",

value: col

}

);

});

And that's it, now you are the omnipotent ruler of the universe, able to kill and create cells wherever you want!

Final steps

The final parts of the rust-wasm book cover time profiling, shrinking the .wasm file size, and publishing to npm. These steps are all relevant to Wavelet apps as well.

Time profiling

You may have noticed that it costs a lot of testnet PERLs to simulate the universe, around 2 million per step! We can apply the same optimization detailed in the Rust Wasm tutorial to cut that down to around 700k PERLs.

Shrinking .wasm size

File size optimization also reduces the cost to deploy contracts, as well as improve load speeds for users, as they still have to download the binaries, so this is also valuable reading.

Publishing to npm

As we have already deployed our contract, there is no need to publish it to the npm registry, as anyone can access it given the deployment address. That being said, we aim to provide a contract registry, and possibly similar wrapper functions that will make it easier to find and use contracts in the future, so stay tuned!

Wavelet Considerations

As we have already deployed our contract, there is no need to publish it to the npm registry, as anyone can access it given the deployment address. That being said, we aim to provide a contract registry, and possibly similar wrapper functions that will make it easier to find and use contracts in the future, so stay tuned!

We currently hard-code the private key to a wallet in our app — this is bad practice as once we publish the code, anyone can access the wallet and drain its funds. As this is testnet, there won’t be a financial loss, but any published version will stop working once if the hard-coded wallet runs out of PERLs.

In order to avoid this, we need to make the wallet dynamic — there are a few ways to do this, namely:

- Randomly generate a wallet, and automatically fund it from a faucet.

- Have the users enter a private key to a wallet that they have funded themselves.

- Use a browser extension that provides a private key/wallet functionality.

Wavelet does not yet have a browser extension — so we cannot use option 3. Option 2 would be the easiest to implement but would make our user’s lives more difficult. That leaves Option 1 — let’s see how we would go about doing so.

To generate a random wallet, we can call the handy generateNewWallet function.

// replace

const wallet = Wavelet.loadWalletFromPrivateKey(/* private key of a wallet containing at least 10 million PERLs*/)

// with

const wallet = Wavelet.generateNewWallet()

This will give us a wallet that will be able to render the universe, but not simulate it or modify it.

In order to fill the wallets with testnet tokens, we can use our free faucet REST API to fill up the wallet.

const publicKey = Buffer.from(wallet.publicKey, "binary").toString("hex");

fetch("https://faucet.perlin.net", {

method: "POST",

body: JSON.stringify({

address: publicKey

})

});

The faucet provides 500k PERLs per request — which means we have to hit the faucet twice to simulate a single step. This isn’t ideal, because the faucet will rate limit us to one call every 10 seconds, and the Game of Life isn’t going to be much fun if we can only update it three times a minute!

Fortunately, Wavelet allows us to deposit gas into a smart contract, meaning that users don’t have to pay gas fees — only the much lower transaction fees of 2 PERLs. We can deposit a few billion PERLs for gas into the contract (join our discord and we’ll happily send you some), which will allow any user to advance the simulation 250k times.

You can deposit gas either through Lens, (the webapp used to upload the contract), or via the JavaScript client by calling a function with a deposit value set:

// run this once - don't leave it in your code!

contract.call(

wallet,

"render",

BigInt(0),

BigInt(1e5),

BigInt(1e10),

);

We also have to make sure that we decrease the gas values currently specified in the existing contract.call options - they are currently 1e7 to allow for enough gas to execute the expensive calls - we can reduce this to 1 PERL.

Now that we no longer store sensitive information in the code, and have a contract with a healthy amount of deposited gas, we are ready to launch the app to the public!

You can see our instance of the universe running here and the final code we have implemented here.